- Published on

The Koko Incident: A Case Study on AGI Ethics

- Authors

- Name

- Rem Elena

The ethical implications of big tech experimentation and artificial general intelligence (AGI) recently collided.

On January 6th, Rob Morris, a founder of the mental health chat service, Koko, started a Twitter thread that detailed the use of GPT-3 in an apparent experiment with the discussion platform. GPT-3, developed by OpenAI, is an API service that allows web and mobile apps access to state-of-the-art synthetic dialog.

The details of the exact experiment are still fuzzy, but here is what we have been told so far:

- In October 2022, an API integration with GPT-3 on Koko was rolled out.

- Users seeking mental health help were not allowed to directly interact with the chatbot.

- Volunteers on the platform who were responding to help requests had the option to have GPT-3 craft a response for them.

- GPT-3 would provide a potential response. The volunteer then had the ability to send that response with or without edits.

- Finally, the user requesting the help would receive the message. A prompt about how “Koko Bot” helped write the message would be included if the volunteer used GPT-3.

- The bot integration was canceled shortly after release, but the AI assistant was used for 30,000+ messages and nearly 4,000 users.

You can see a demo of the process here.

Rightfully so, once these details became known, many were angered and concerned by the ethical grievances Koko potentially committed. Experimenting with AI in a field known for human sympathy and compassion left a bad taste in many a mouth. I, too, have passionate feelings on the topic and will try to express them in as constructive a manner as I can.

Sadly, my disappointment is not limited to simply the news itself. Articles covering this story appearing on NBC and other digital media outlets truly lack depth in several arenas. None of them are entirely false, but they all lack what I consider to be a fair representation of what might be the truth.

In the remainder of this post, I hope to untangle both the larger story and my own emotions regarding the entire matter.

Experimentation In Plain Sight

For some, this story was perhaps the first time they had encountered a tech company conducting an experiment on its users. Unfortunately, this is in no way the first time, and it likely will not be the final time.

The history of experimentation on unsuspecting consumers dates back well before the Internet. For decades, corporations have relied on tweaking and changing things right under our noses in an effort to improve their bottom line. These activities can range from seemingly minute changes in advertisement to broader campaigns targeting a specific region or even town.

Ever grabbed a “limited edition” soda flavor that was never seen again? More likely than not, that was an experiment done to gauge that product’s success in a broader market. In some regards, the open market might be the biggest Petri dish of them all, and we are all under the microscope.

What makes an experiment ethical?

For those familiar with medical or academic research, terms like informed consent and Institutional Review Board immediately come to mind.

Informed consent is a deceptively simple term. In the context of an experiment, it means that the participant acknowledges the potential benefits or dangers of partaking in the research and still agrees to continue to cooperate. The sticking point usually is for an ethical researcher to convince themselves the participant has the capacity to understand the risks and the capacity to provide consent. Certain populations are incapable of providing unconditional consent; for example, children, prisoners, and severe mental health patients. Similarly, potential participants who are not properly educated on the risks of the experiment cannot be deemed informed.

If there are so many potential hazards and concerns, how do researchers successfully obtain informed consent?

This is where Institutional Review Boards, or IRBs, come in. IRBs review aspects of an experiment to evaluate any areas of concern, including factors surrounding informed consent. The board considers the potential participant population, the onboarding materials to educate participants, the wording of the consent forms themselves, and many more dimensions of the process. Additionally, researchers provide ample proof and documentation regarding the safety, efficacy, and intent of their experiment. Ultimately, if the materials and preparations are sufficient, then the IRB provides its approval and the research can get underway.

Do concepts like this even apply in the laissez-faire world of capitalism?

In the United States of America, no laws currently exist fully constraining a company’s decisions to experiment on consumers. Partial laws exist to prevent certain industries, like pharmaceuticals, from developing products without some government oversight. But, for other sectors, especially technology, few laws are in their way. This lack of oversight is terrifying, but that terror only is expounded when you consider the ease of contact digital products have with consumers.

Unlike an experimental soda flavor, where products need made and physically delivered to potential consumers, companies offering web or mobile applications are free to change things instantaneously, almost on a whim.

Repetitive experimentation is synonymous with modern app development. In fact, there is a common practice in the software industry called “A/B testing”. A/B testing quite literally splits users into two experimental groups. The “A” group receives a version of a feature, while the “B” group gets another experience. Sometimes the users are aware which group they are in, most of the time they are not. Consent is typically discussed like: “Were users forced to use the app? No? Then they were consenting.”

And the experimentation does not stop with just feature development. The last decade has seen several big tech companies conducting broader human behavior experiments. An often cited example is when Facebook played with users’ emotions by controlling their feeds.

When discovered, Facebook pointed to its Terms of Service to prove they did no wrong. Within the terms were clauses indicating user acknowledgment to potential experimentation. However, a TOS agreement that the majority of users never read would never satisfy the conditions of informed consent or an IRB approval.

Despite press coverage and public outrage, no real changes have been made to protect consumers. In the end, it is up to tech companies themselves to self govern when an experiment is acceptable or not.

Legal Shades of Gray

As I mentioned earlier, medical technology is one area where partial laws do exist. In the realm of pharmaceuticals and other treatment experiments, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) serves as the main regulatory body. Traditionally, the FDA provides ethical oversight for the research, development, and durability of experimental drugs, diagnostic devices, or other medical equipment. Recently, this oversight has extended to apps and software for the diagnosis and treatment of mental health conditions.

Not every health and wellness app falls under FDA regulation, however. According to current FDA policies regulating medical devices, FDA clearance is required if the app is used “for diagnosis of disease or other conditions, or the cure, mitigation, treatment, or prevention of disease”.

This policy is easily interpreted for somatic illnesses like diabetes or heart disease. If the app is directly measuring, diagnosing, or providing interventions for the patient, then it is a medical device. But, what about mental health conditions? What constitutes a treatment for a psychological condition?

Koko provides users the opportunity to seek support for difficult emotions that may or may not be related to mental health conditions. At no point does the app seek to diagnose the user based on their conversations. Nor does it provide users access to professional consultation or talk therapy. The entire service is volunteer based. Although therapeutic, discussing challenging feelings with someone else is not treatment, whether done at your local bar or via a chat app.

The lack of mental health professionals on the platform is seemingly by design, too. Koko’s entire inception stems from its founders recognizing the huge disparity between those needing help and trained therapists able to provide the help. The app was made to allow someone stuck on treatment waiting lists to have supportive conversations in the meantime.

All things considered, Koko falls outside the scope of FDA’s definitions of a medical device, in my opinion. At worst, Koko could be considered “treatment aligned” in that it seeks to provide a supportive, beneficial service that just so happens to mimic aspects of the benefits of talk therapy.

And so, Koko's decisions to experiment on its users are largely outside the purview of governmental constraints. Koko's leadership held the sole responsibility of determining how ethical their plans were.

Koko Knew Better

Even if Koko falls outside of FDA scrutiny, I would be remiss to not criticize their behavior here.

The service is specifically welcoming to a marginalized group: those suffering from a mental health condition. While having a mental health condition is not a requirement to use the service, the marketing and branding makes it entirely likely that those who start a chat are those diagnosed with some kind of condition.

Experimenting on anyone without their consent is a terrible grievance. Doing so against a population that might already be struggling with perceptions of reality, distrust, and hopelessness feels incredibly evil. The real cherry on top here is that the experiment Koko tried was in removing the human connection their platform promised to provide.

As I discuss in another post, AGI has historically presented unpredictable and sometimes harmful outputs, especially for those in marginalized groups. While ChatGPT (which utilizes its own version of GPT-3) proved to have decent safety protocols in place, using it as a conversation assistant for mental health support is another issue altogether.

Leaders within Koko also are no strangers to proper researcher ethics and protocol. The platform was the result of experiments run in a MIT lab. Additionally, the Koko website lists several academic publications, which most certainly had to undergo peer review and potentially IRB approval.

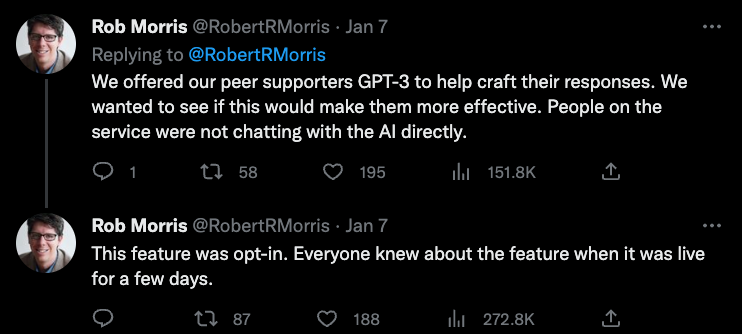

After the initial uproar on Twitter, further details were provided which might resolve some ethical concerns. One tweet states the feature was “opt-in” and that all involved were aware while the feature was live for a few days.

No proof of this opt-in process or its wording have been provided.

Koko prides itself as being an experienced member of the “Trust & Safety” community. Trust is a fragile thing. Providing confusing, terse after-thoughts on important conditions like consent and permission makes me question my trust in Koko.

The Forgotten Enforcer: OpenAI

So, given all the evidence available on Twitter and through demos, it seems like our worst fears are confirmed? It appears a trusted online help provider seemingly forgot decades of previous research experience and ethics and conducted an AGI experiment on a vulnerable population. Grab the metaphorical megaphones and start the protests, right?

I understand, and urge us to wait.

I believe Koko made a huge communication misstep. They fumbled big time trying to inform the wider community about the false success AGI has in mental health conversations. I cannot convince myself, however, that Koko acted maliciously. Key founders and leaders in the project have come across as dismissive and self-righteous, but we have to acknowledge the fact that this information was willingly shared. Someone convinced they did something wrong would not likely do this. It is what we do not hear about that should concern us more.

I am also willing to believe that proper communications were given to all users involved, and that these communications indicated potentially receiving messages written by synthetic AI means. However, I do doubt any such messaging would satisfy rigorous evaluations of informed consent.

Overall, I am not convinced that the worst-case scenario occurred: that some malevolent tech company covertly deployed AGI in an attempt to subvert user perceptions for capital gain.

I am able to have these beliefs because OpenAI, not Koko, is the one with the most to lose here. AGI’s success is still new, and with all new things, change can by unsettling. GPT-3 is an incredibly powerful tool, and OpenAI is not in the business to allow anyone to have free rein over its use. To fulfill its mission to see AGI benefit all of humanity, OpenAI must be vigilant and prepared to combat potential abuse.

At the time of Koko’s integration of GPT-3, OpenAI was still requiring manual approval of API usage. Part of this approval process would have involved a human confirming the compliance of OpenAI’s usage policies. Of note, these usage policies explicitly prohibit the non-consensual use of GPT-3 in chat settings. (Note: these policies have since changed to remove the human-in-the-loop component. I assume they managed to automate this process and usage compliance checks still occur.)

It is entirely possible that the process failed, things fell through the cracks and Koko did end up doing something incredibly harmful. But, I also have inklings that OpenAI is more than capable of detecting misuse very rapidly. Perhaps this is why the Koko experiment only lasted a few days before being shut down?

Restoring What Was Lost

AGI’s accessibility to developers and businesses is reaching unprecedented levels. Every economic sector and academic specialty will benefit from the innovations and advancements the technology will allow. Excluding AGI from certain use cases is, of course, warranted and extremely important. For applications on this edge of acceptability, such as in mental healthcare, what is the appropriate path forward?

Koko’s founders are correct in that there are not enough trained professionals to accommodate the crisis we are facing with mental health. Providing these professionals with innovations would likely save countless lives. Simply doing nothing might be the worst evil of all. Technology has a role here that can be molded to benefit everyone.

Do I believe the core question Koko tried to answer was appropriate?

Yes, I do. I absolutely think evaluating the therapeutic efficacy of synthetic support chats is a reasonable endeavor. I do think that given a preference between human versus synthetic, most would opt for the human, even if they are slower to respond or have more errors. However, there is still the possibility that a certain group would feel it easier to have difficult conversations with a synthetic source. It would be just as unethical to not acknowledge and support such a preference.

Do I believe Koko was the best avenue to pursue this question?

No, 100% no. Koko saw an opportunity and decided to forego appropriate ethical considerations. As an at-risk population, mental health patients need the utmost caution and respect in research. I believe any research to be done on this population needs to be done at the hands of licensed professionals, under the full scrutiny of an IRB, and with full informed consent. Anything less than this will undoubtedly allow potential abuse to occur.

Do I believe media coverage got this story wrong?

Sort of. The NBC article certainly provided a great summary for readers to understand the current loopholes tech companies have to potentially exploit regarding user experimentation. However, the article failed to include important clarifications Koko provided that would have de-escalated the doom and gloom tone the article voices. As with many news pieces, this article sadly provided readers with information at the cost of influencing the reader’s perception of that information. Part of my motivation for writing this article was to try and provide a more holistic perspective on the story.

Overall, I still have mixed feelings on this entire incident. I hope proper communication did occur and no user felt tricked or overtly experimented on. Even if done with no malicious intent, I fear this Koko mishap has chilled many people’s willingness to trust other AGI use cases. Any obstacle to people accessing something that might help them feels cruel and tragic.

I sincerely wish to see AGI successfully improve lives, but this process requires trust. Mistakes and poor communication will be costly. Whether one faults Koko for its use of GPT-3 or its way of telling the public about it, clearly trust was lost.

To their credit, members of Koko have turned this entire incident into an opportunity to share and communicate best practices and feedback with the larger AGI community. It is through actions like this that I think trust can be restored.

Similarly, I do have faith that some of the most brilliant minds in this industry are tackling difficult topics in the realms of AGI usage and how to prevent misuse or abuse. As long as there are those professionals willing to have empathy for users and put ethics into their work, I think they deserve more of our trust.

The prevalence of AGI in our everyday lives will soon be the norm rather than the new. Industries will likely continue to make mistakes trying to figure out how AGI fits in their broader products. Experiments will continue, and it remains to be seen how well-communicated these experiments will be. Again, it is the experiments that occur without any public report or debate that worry me the most.

It is more important than ever for each individual to evaluate which tech companies they are willing to offer their trust to. Likewise, it is up to these companies to honor that trust and proceed with caution and compassion.